0.3 Introduction to canisters

Smart contracts on ICP are known as canisters. A canister contains both program source code and its corresponding state. A canister's source code is compiled into a WebAssembly (Wasm) module, and then that module is installed into the canister. Once a canister has a Wasm module installed, it can be deployed to the network for end users or other canisters to interact with.

WebAssembly is a low-level computer instruction format. It abstracts a program's execution cleanly over most modern hardware. WebAssembly is portable and broadly supported for programs that run on the internet, making it a natural fit for dapps intended to run on ICP.

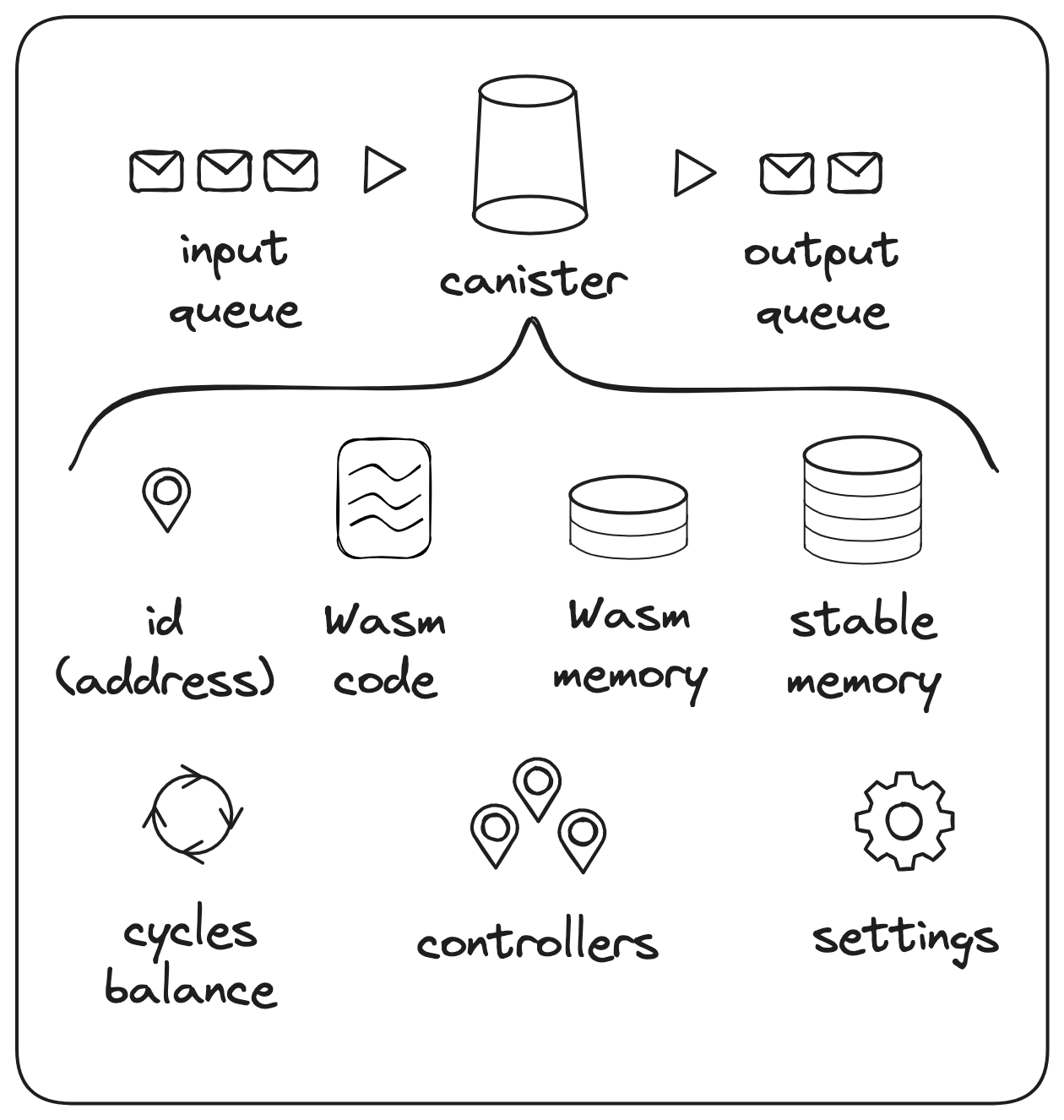

Canister architecture

Canisters have additional components alongside their Wasm code. These components are outlined in the diagram below.

Canisters can be developed in a variety of existing languages, such as Rust, JavaScript, Python, and TypeScript. There is also an SDK for Motoko, a language specifically designed for canister development on ICP with a focus on programming in a distributed asynchronous environment.

You'll dive further into Motoko and other languages in the next section, introduction to languages.

Types of canisters

Backend canisters: The backend of an application hosts the application's primary source code and functionality. Backend canisters can be written in Motoko, Rust, Python, or other programming languages. When a project is created with

dfx, the file structure for a default backend canister is created within the project's directory.Frontend canisters: The frontend of an application is the user interface. Frontend assets typically contain CSS, HTML, JavaScript, or React elements. Frontend canisters are compiled into Wasm using an implementation of the asset canister. When a project is created with

dfx, the file structure for a default frontend canister is created within the project's directory.Custom canisters: Custom canisters don't fit into the frontend or backend canister type definitions. These may include a mix of backend and frontend functionalities, or they may be used for specific, individual functionalities within the dapp.

Project architecture

When designing a dapp, one of the first decisions you should make is how to structure it. Should it be within a single canister, or should it consist of multiple canisters?

If you're developing a simple service-based dapp that doesn't include a frontend interface, a single canister might be a good choice to simplify project management and maintenance.

If your dapp is intended to have both frontend assets and backend logic, your dapp should contain at least two canisters. This is the default structure that is generated by dfx when a new project is created.

It also may be beneficial to separate different reusable services into their own canisters so that they can be imported and called from other canisters or be made available to other developers. For example, a dapp that provides a social media platform might split the backend functions into two canisters: one that contains the code used to establish social connections and one that contains the code that is used to set up user profiles. Additionally, a third canister may be added that provides functionality to schedule social events or create user groups.

Canister communication

Canisters communicate with other canisters through the use of asynchronous messages. Each message is executed in isolation, which allows for increased levels of concurrent execution. Canister messages are either outgoing requests or replies to incoming messages. When a canister processes a message, the result of that process could be a change to the canister's state, a reply message sent to another canister, or even the creation of a new canister.

If a canister processes a request that requires the canister to send additional requests to other canisters, the canister may wait for the replies from the other canisters before producing a reply to the original request. If a canister fails to respond (referred to as 'trapping'), the requesting canister's state is rolled back to the point right after it made the last outgoing request.

Canister controllers

Canisters are managed by controllers, which may be a single user, a group of users, or another canister. If a canister has no controller, it is immutable. A canister can have multiple controllers.

A controller is the only entity that has permission to manage the canister through workflows like deploying the canister or starting and stopping the canister. Controllers can also change the canister's parameters, add or remove additional controllers, or delete the canister.

Additionally, controllers can upgrade the canister code by installing a new Wasm module to replace the current module. This allows developers to change, update, and continue developing their dapp after it has been initially deployed.

Canister fees

A canister's controller is responsible for ensuring the canister contains enough cycles. Cycles are used to pay for the canister's resources, such as memory, computational power, and network bandwidth. Each operation that is performed by a canister has a cost of cycles. A canister has a local cycles balance used to store the canister's cycles.

For memory usage, the system keeps track of all memory used by the canister and regularly charges the canister's cycles balance. This charging happens at regular intervals for efficiency.

For computational power, cycles are charged at the time computation is performed. Each canister contains instrumental code that allows ICP to count the number of instructions executed during the processing of a message. Each round, there is a limit on the number of executions that can be performed during that round. If that number is exceeded, the execution is paused and continued in the following round. Cycles for the computation are charged at the end of the round. For security and efficiency reasons, there is a limit on the total number of rounds the execution can use.

For network bandwidth, cycles are charged at the time of usage. When a canister goes to send a request to another canister, the system automatically calculates the total number of cycles that sending the message will cost. This cost consists of a fixed component and a component that varies based on the size of the message's payload. This cost is then deducted from the canister's cycles balance. A charge is also deducted for sending a maximum-sized reply to a callee, since for inter-canister messages, the caller pays for the reply. Any cost difference between the maximum size and the actual size of the reply is refunded to the canister when the reply arrives.

If a canister runs out of cycles, the canister is uninstalled. To avoid this, canisters have a 'freezing threshold.' If a canister's balance dips below this threshold, then the canister will stop processing any new requests. Replies will still be processed. The system will throw an error if the canister attempts to perform any action that would result in the canister's cycles balance dipping below the freezing threshold.

Need help?

Need help?Did you get stuck somewhere in this tutorial, or do you feel like you need additional help understanding some of the concepts? The ICP community has several resources available for developers, like working groups and bootcamps, along with our Discord community, forum, and events such as hackathons. Here are a few to check out:

- Developer Discord

- Developer Liftoff forum discussion

- Developer tooling working group

- Motoko Bootcamp - The DAO Adventure

- Motoko Bootcamp - Discord community

- Motoko developer working group

- Upcoming events and conferences

- Upcoming hackathons

- Weekly developer office hours to ask questions, get clarification, and chat with other developers live via voice chat.

- Submit your feedback to the ICP Developer feedback board